Having the “right” friendship is sensational. Some might come and go, while others can continue flourishing into meaningful unions.

Speaking of the latter, and the word “right”, friendships allow those involved to grow and cultivate opportunities by merely having a conversation. Have you ever freely chatted with your friend, then suddenly have a light bulb shining luminously above your heads because a brilliant idea is doable for you two? That’s what I assume occurred between Eric Buvelot and Jean Couteau.

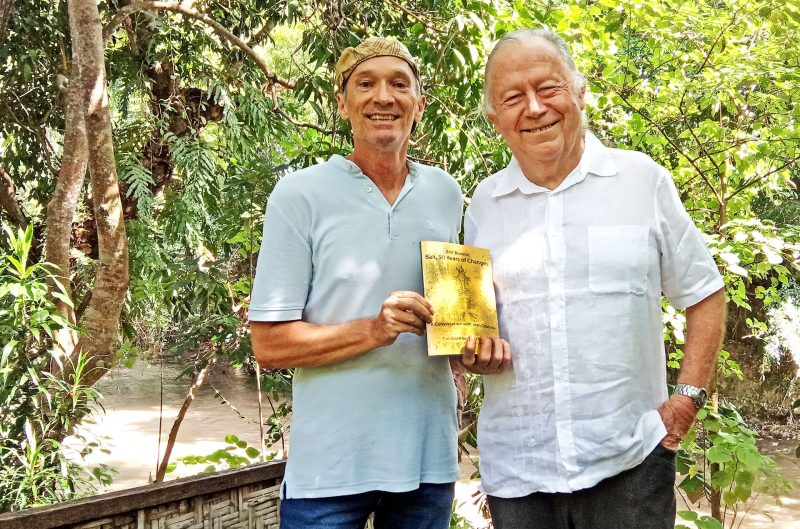

My turn to have a conversation with Buvelot. As the author of Bali, 50 Years of Changes, Buvelot sat down for long hours and days with his long-time friend Couteau, a fellow Frenchman who’s also lived in the island of the Gods for the last few decades. They’ve practically never left Bali, which sparked up their mutual desire to do this project together.

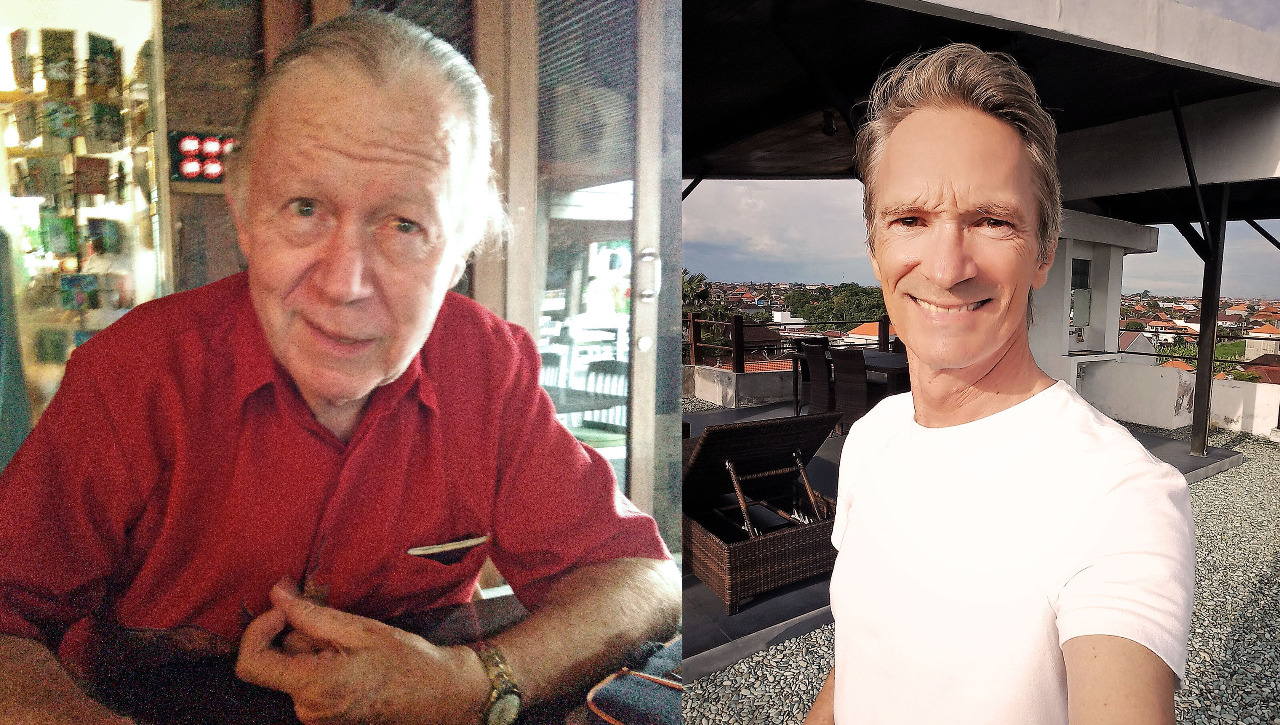

Jean Couteau and Eric Buvelot

Jean Couteau and Eric Buvelot

Buvelot’s time in Indonesia started in 1995. He finds life in Indonesia serving marvellously despite any possibilities of it turning sour. It’s the life he chose a long time ago, much to what he wanted. He’s even become an Indonesian citizen since 2016. “I should be better called an inpatriate than an expatriate, don’t you think?” he pointed out. Couteau’s arrival in Bali was during the metamorphosis era in the 70s – tourism called on Bali’s warm name to the world, thus boosting Indonesia’s economic development. He’s seen, heard, and experienced Bali in ways not even Indonesians have come to realise.

Flipping through 289 pages front to back made me wonder, to what extent does Buvelot lean on Couteau’s insight of modern life impacting Balinese society? He admitted that different opinions on the changes occurring in Balinese society were portrayed between them. But he went on to clarify, “To a complete extent. I’ve written hundreds of articles about Bali for so many years. It’s obvious that this island has sacrificed many aspects of its culture and traditions for the sake of capitalist developments through tourism businesses. The impact of modernity has been huge, like on any other small island community in the world. Denying this fact would be a complete political mistake.” Two aspects support his view: Bali has indeed resisted better than any other “paradise island” in the world, yet the damages have been serious on many levels, from cultural to environmental. The local mainstream overlooks or minimises said changes all in the name of growth.

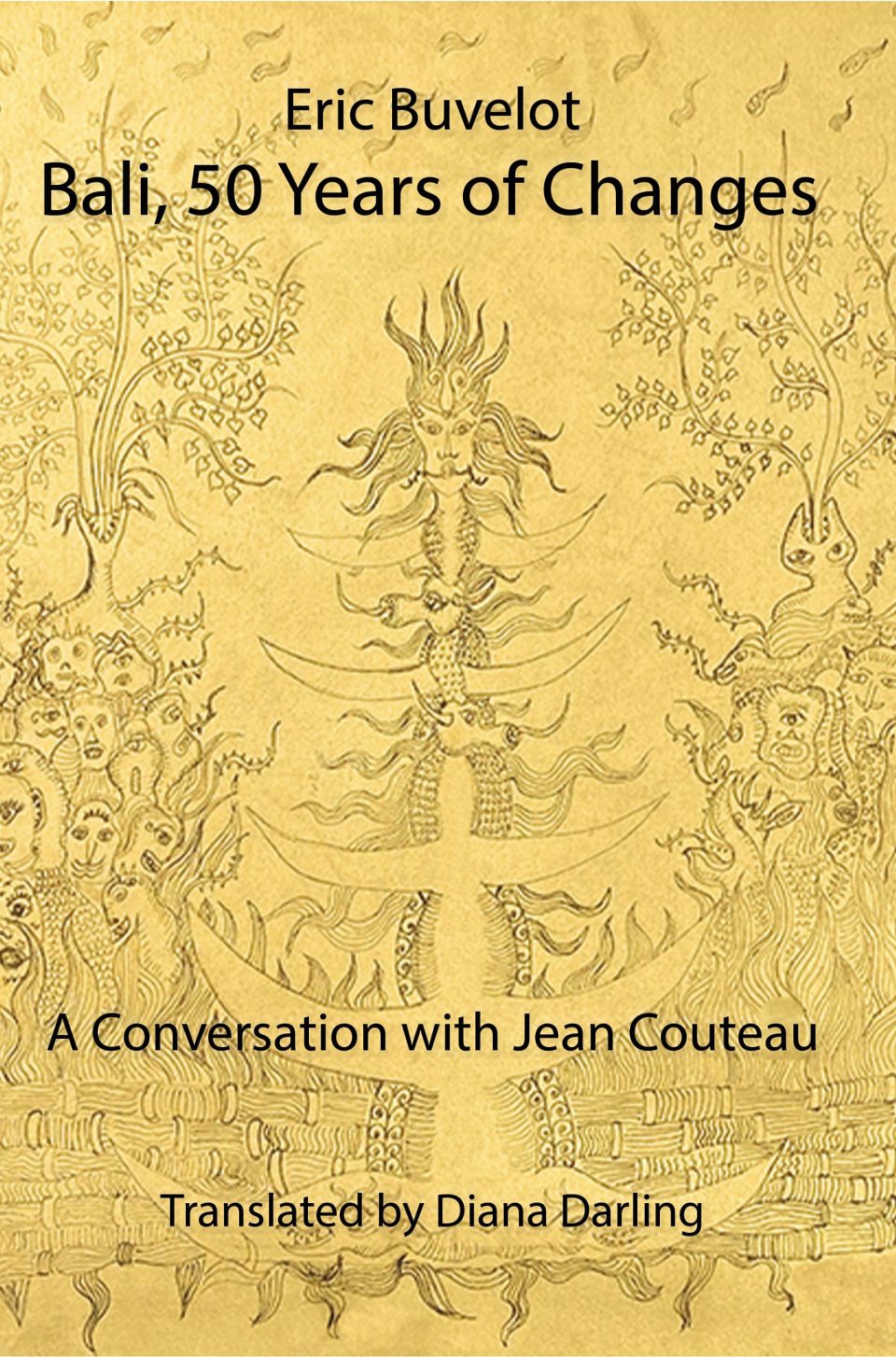

Buvelot describes Bali, 50 Years of Changes in three words: Bali, sociology, Jean Couteau. This book represents interviews – I’d like to call it conversations between friends regarding their observational revelations instead – on socio-historical terms as they’re within the sociological object being analysed. Two expats talking in-depth about Bali may not cohere but interestingly, they conceptualise Bali’s “fantasised society” with alarmingly undiscussed insights reeled in from inside and outside the realm.

Two inspirational factors come into hand, explained Buvelot; “the desire to do something with Jean Couteau and the need to do a major work about the many upheavals Bali had come through since several decades.” Buvelot had interviewed Couteau several times for La Gazette de Bali. “Jean shared this desire, and once we managed to have enough time for a project together, we started to work,” he added. Nothing sort of this book had ever been done before either. Buvelot strongly believes Couteau was the right person to work with, right now. See, friendships can forge desires into reality!

A lot to unravel about the island’s changes. Buvelot took the approach of a Q&A format instead, thus, their conversations weren’t composed as scientific findings. “I wanted the book to be readable by anybody, at any chapter, at any page, even at any paragraph. I didn’t want a result that looked too academic. It’s still a very serious book, but with the Q&A format, we drifted away from this usual scientific, and sometimes boring, form of work,” he pointed out.

Couteau is a scholar but they didn’t want a scholar project composed since this book is also about Couteau too. The questions asked by this seasoned journalist empowered Couteau as another main subject, therefore highlighting his legacy on Bali studies. The English-speaking sphere of Bali experts and important intellectuals in Indonesia, he added, are familiar with Couteau but it’s high time the rest of the world joins.

The book is divided into four parts based on the principles controlling the four aspects of life in Hinduism: kama, arta, darma, and moksa, adjusted appropriately on the island’s recent sociological metamorphosis. Their rhetorics according to the many aspects of the human psyche towards life depicted their starting point to construct the book.

Part One: Kama

Part One: Kama

They openly discussed – similar to all parts of the book, depending on the topic – about the social construct of the olden and modern days. To say the points mentioned are common topics amongst expats and the locals converse daily is vague. “I’m not sure locals and expats discuss the things we discussed in our book. Or if they do, as anyone is entitled to have an opinion, they might not apprehend sociological concepts to the depth we sometimes reveal or even decipher them,” expressed Buvelot.

“If the topics we take on belong to daily conversation among locals and expats, these conversations might then lead to more misunderstanding. Hence, the purpose of our book is to shed light on the sociological evolutions on the island.”

Part Two: Arta

Someone who comes to Bali in the modern days would be appalled to learn the points mentioned in Arta. I am that “someone”. Realising what was then and identifying what is now in terms of tourism, economy, over-exploitation, etc could merely foster catastrophe. Bali in the next 50 years might reach self-destruction if this current pace is maintained, said Buvelot.

“In developing nations, there is a terrible dichotomy between the need for growth and the necessity to preserve what makes their identity. For the sake of making money, they might forget what makes them what they are. In between these two imperatives, developing countries are at risk to lose their way. This is where the challenge is!” he added.

Part Three: Darma

“Morality” caught my attention simply because many tourists are popping up in the local news outlets lately since Bali’s international doors have reopened. Misapprehending their lack of morality towards the Balinese customs, religion, and overall livelihoods has been causing uproar not merely to the Balinese but also to Indonesia as a whole, and even the expats residing. Perhaps Part Three can give tourists better understanding, I reckon. Education is after all vital for individual and societal development. This book has the potential to give some insights into a better relationship between Bali and the rest of the world.

Not losing one’s way, according to Buvelot, is by welcoming the whole world on your “paradise island” not merely for financial profit because individuals who have completely different ideas on the concepts that construct a community’s identity is the foreseeable outcome. Culture shock. Taboos might not coincide with other world cultures. Nudity in your home country could be acceptable but at a sacred tree or a temple dedicated to fertility in Bali?

Bali grasps dearly to an appeasing relation to otherness. The two weighing on this tolerance towards “the other” might be in danger as identity politics are on the rise in Bali. “Jean and I have a different perception about the outcome in the longer run. I appear to be more optimistic, but who knows? Are nowadays tourists still interested in Balinese otherness? Balinese culture and worldview? Selling the island to mass tourism or elite tourism, both ways having been explored lately, one detrimental to the other, is by no means the right way to encourage cultural tourism,” he conveyed.

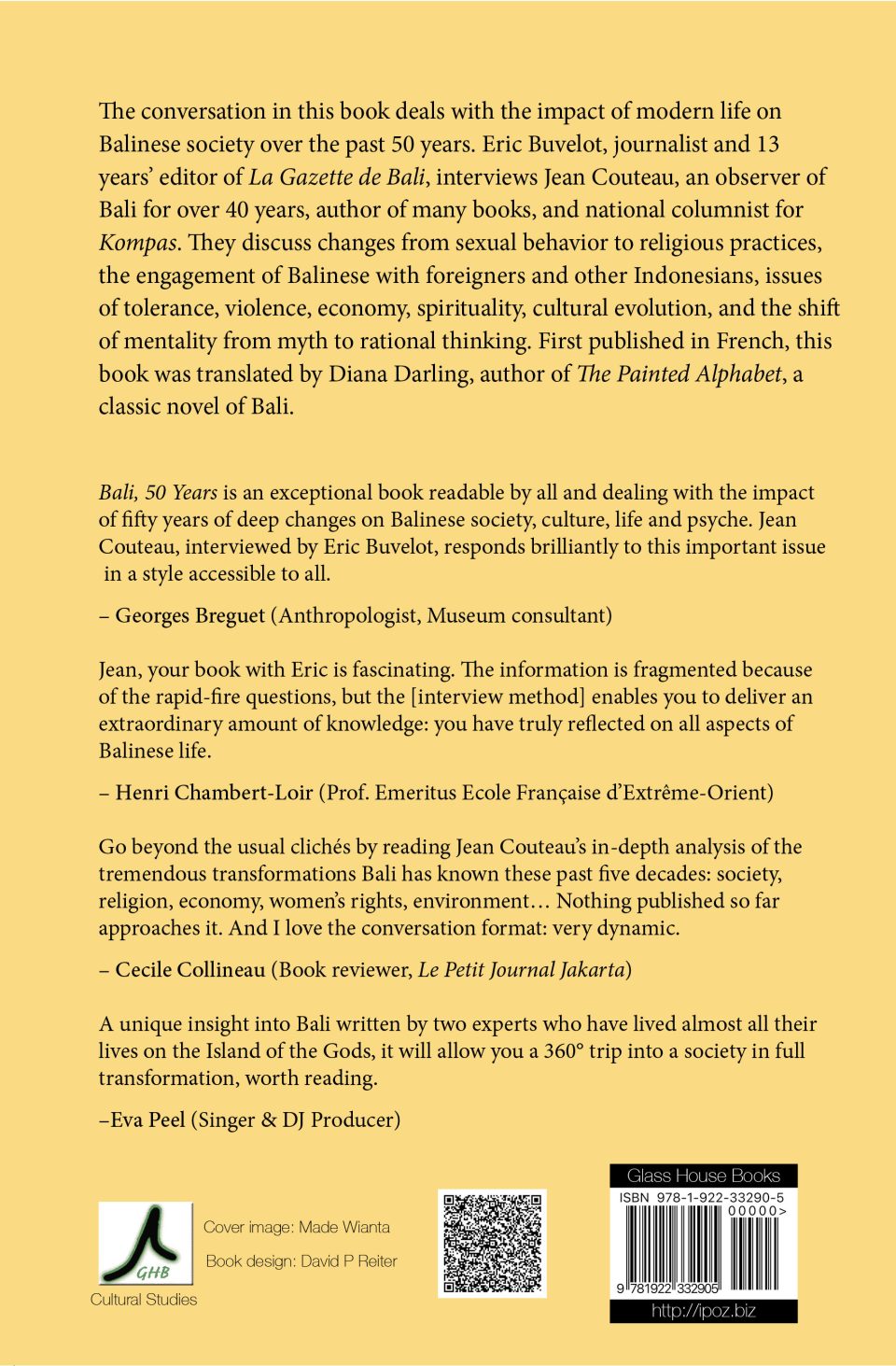

Bali 50 – Years of Changes

Bali 50 – Years of Changes

Part Four: Moksa

The elaboration on religion in Moksa marks significance to the Balinese. The book suggests that Balinese religion needed to be defined in history as Indonesia came into a republic nation. Nowadays, Couteau explained it’s still redefined. “Balinese religion has been labelled Hindu in the early years of the Republic, but was it really? Originally, it was mostly a cult of the ancestors with Hindu aggregations coming from Java. Is this syncretism something of the past? It’s true that Balinese religion has been mutating with a move towards a more normative Indianized Hinduism lately. Something orchestrated by local religious authorities. It’s an important change that needed to be discussed and recorded in our book.

The relation with the West section is intriguing. As a Westerner, what are your views of Bali’s metamorphosis you’d like to add on?

-I think that what we put in the book is quite complete… The relationship that Indonesia as a whole has had with the Western world through time deserves a million books! But Bali has this very unique relationship with the West. Maybe because of how much Bali fascinated the early Westerners who visited it. Somehow, the Balinese have been caught in what I call a “narcissist trap” with the West. And until today, they still try to fit in this touristic vision of paradise on earth! Otherwise, locally, the Balinese became some sort of experts on the rest of the world. There is a very obvious reason for that: the whole world is regularly invited to their island! The ordinary Balinese are simply very accustomed to other populations.

Do you think the continuous shift of mentality from myth to rational thinking will outshine all the things that make Bali as it is? Please justify.

I hope not because something invaluable will be lost! The uniqueness of this island. But isn’t it the inevitable fate of our global world to follow the same capitalist model everywhere? Whatever your beliefs and traditions were… This is the great strength of capitalism, if it doesn’t destroy your values it can accommodate them.

I asked Buvelot to fill in the blanks of “Bali: 50 Years of Changes is recommended for expats and Indonesians because”. He said, “it will give you an insight on how the Balinese have managed to adapt to a seismic upheaval like no other during the last decades when nothing had changed much previously for about a millennium.”

This book is available in French and English. You can grab a copy on Amazon or on Gope-editions for the French version.